The Atlanta Hawks of the late 1990s were incredibly unique, loaded with talent and depth but overshadowed by better teams around them.

None of the starting five that included Dikembe Mutombo, Christian Laettner, Tyrone Corbin, Steve Smith, and Mookie Blaylock was drafted by the organization. Their talents were all imported from other cities to a city that got its start as a train depot.

The last to arrive was Dikembe Mutombo. He signed with the team on July 15, 1996. That’s 43 days before Outkast released its second album Atliens. By the time Outkast released Aquemini in September of 1998, the Hawks in discussion had already peaked. There would be no Stankonia, and I’m so sorry to say, Ms. Jackson, that by the fall of 2000 only Mutombo would still be on the roster. He would be traded to Philadelphia before the end of that 2000-01 season. He would make a Finals, but the Mutombo teamed with Allen Iverson was already suffering from erosion.

Much is often made about how Michael Jordan and the Bulls came of age with the city of Chicago. His rise coincided with Oprah’s television takeover. Both were building empires, and while no one knew it at the time, a future president was also calling the Windy City home. The city was even featured prominently in an ABC sitcom. Before watching the Winslows put up a front door defense against Steve Urkel’s nasally snort, viewers saw the glimmering waters of Lake Michigan and a near flawless skyline built on big shoulders.

Atlanta at this time had Matlock, the Atlanta Braves, and Deion Sanders. Sanders was an individual delight, but Andy Griffith was a seersuckered, past-his-prime lawyer who in a faster-paced city probably would have been investigating his own murder. And the Atlanta Braves, while thrilling in 1991 and champions in 1995, largely erected a legacy that was more peach bruise than Big Apple. There’s a reason Andre 3000’s “the South got something to say” resonated against the powers that be: the chip on his shoulder was regional.

From 1972 until 1995 the Atlanta Hawks logo possessed a closer resemblance to Pac-Man than an avian spirit animal. Moreover, the most memorable moments in that chunk of time for the franchise were synonymous with the fanciful ballhandling of Pete Maravich and the acrobatics of Dominique Wilkins. Toss in Spud Webb for good measure, but all in all, Atlanta basketball was all about style. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, but neither is it anything for the history books.

In the epoch prior to Dikembe Mutombo’s arrival, the Hawks put up some very good teams against some very great teams, and the results were to be expected. They lost playoff series to eventual champions. They lost playoff series to the Milwaukee Bucks. When Lennie Wilkins was named the head coach, a purging of the roster commenced. Dominique Wilkins and Kevin Willis were old. It was time to get serious. A New Atlanta was on its way.

The Atlanta Hawks’ Dikembe Mutombo (L) is fouled by the New Jersey Nets’ Michael Cage (R) as he drives towards the basket in the first quarter 31 March at Continental Arena in East Rutherford, New Jersey. AFP PHOTO/Matt CAMPBELL

When Dikembe Mutombo came to Atlanta

The 1995-96 season saw the nearby Atlanta team represented by a red raptor with outstretched feathers — its talons clutching a basketball in midflight — rather than a duck-rabbit equivalent. This shift in logo logistics did not mean the team had found an heir to Dominique’s airborne mystique — after all, Danny Manning, knee injury and all, had already limped through town on his way to signing with the Phoenix Suns. No, that time of undaunted flight was being left in a bygone decade that was still too close in proximity to spark nostalgia. Jon Koncak and Tree Rollins who? Instead, the team planned on following its new cartooned messenger with wings by announcing a no-fly zone.

In a 2015 tribute to Mutombo’s Hall-of-Fame career, Chris Vivlamore wrote of the circumstances that made Mutombo a necessity in the eyes of Atlanta’s front office:

The Hawks needed a shot-blocking, rim-protecting center following the 1995-96 NBA season. Enter Dikembe Mutombo. He was the focus that summer of an organization looking to complete a rebuild and change its playoff fortunes.

The Hawks needed Christian Laettner to play center during their 1996 playoff run, which started with a series win over Rik Smits and the Pacers and ended in the next round with a loss to Shaquille O’Neal and the Magic. O’Neal outscored Laettner 139-77 and outrebounded him 57-26.

The plan fell into place perfectly. Mutombo signed a five-year deal for $55 million dollars, and the franchise had come full circle, going in a starkly different direction from its previous attempts at contending, and a great deal of finger-wagging was about to commence throughout the great state of Georgia and beyond.

Christian Laettner’s lone All-Star appearance happened in his first year playing with Mutombo. Not only did Laettner’s scoring spike but so did his rebounding. A Hawks broadcast often featured commentary about how Laettner needed to play tougher as well as constant theorizing on what a consistent offensive game could do for Mutombo. As theatrical and effective as the finger wags were, Mutombo existed somewhere just outside the circle of the league’s most elite centerpieces.

Each player in Atlanta’s frontcourt possessed a weakness and a strength the other did not possess. Together they were a Jerry Maguire-pairing, but by the next season, the partnership would lose its vitality. Injuries would start to plague Laettner. Alan Henderson would start getting more run, and by the 1998-99 season, Laettner was in Detroit with Grant Hill and evermore the role player.

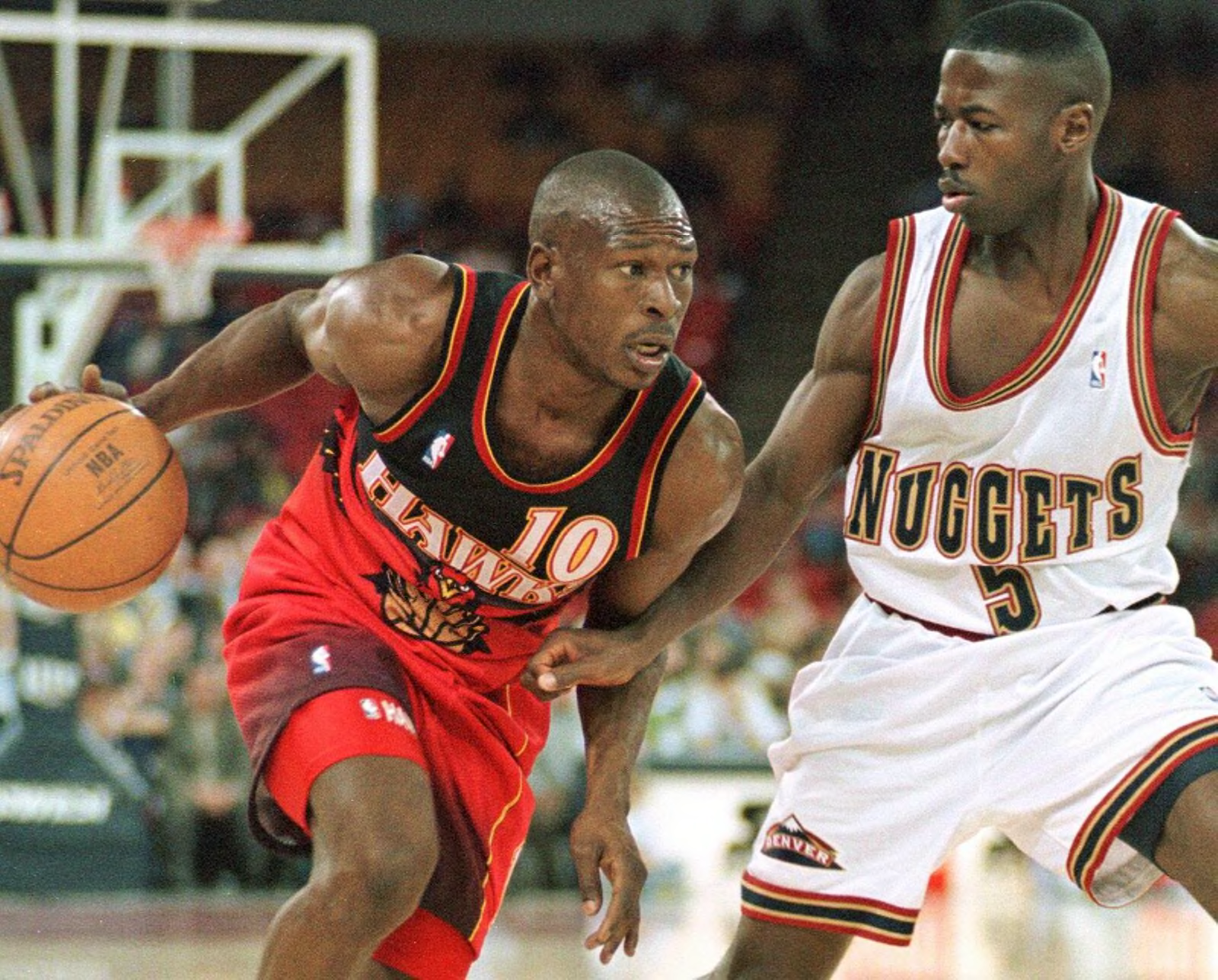

Atlanta Hawks’ Mookie Blaylock (L) drives past Denver Nuggets’ Anthony Goldwire (R) during first half play of their NBA game 25 February at McNichols Sports Arena in Denver. AFP PHOTO/Doug COLLIER

The real foundation for the Atlanta Hawks brief moment in the sun was the backcourt

Some nights shooting guard Steve Smith rarely dribbled. Other nights he’d pound the ball, probing the defense for that soft spot in the midrange. He dunked maybe once in his career. He ran curls around the elbow. He waited beyond the arc. He spotted up. He made shots — lots of shots. And he played in such a manner that everything was a warmup. He could have played in a suit and tie. He led the team in scoring and carried himself like an NBA analyst on the court, but his fans carried signs that read “Smitty Happens.” He was an antecedent to Klay Thompson, although he probably wasn’t quite the defender. He wasn’t a bad one, though. He also didn’t have a Splash Brother — he had Mookie Blaylock.

Blaylock was an All-Star in 1993-94, racking up 9.7 assists per game that year. In 1997 and 1998, he led the league in steals. Basketball writers sometimes stick him with the journeyman label or as a footnote in Pearl Jam’s lore, but the labels don’t quite do Blaylock’s quick-handed smoothness any justice. Because he only played for three franchises, the journeyman label is something of a misnomer, and in the four seasons between Dominique Wilkins leading the Atlanta Hawks in Win Shares and Mutombo picking up the mantle, Blaylock carried the majority of the franchise’s weight. In Dominique’s soon-to-be twilight, Mookie was the guy worth keeping, and yet entrusting him with an entire franchise proved to be a difficult ask.

Around the same time the Atlanta Hawks transformed the franchise’s logo, head coach Lenny Wilkins “sat Blaylock down for a concerned lecture after his 1995 arrest for DUI, carrying an open alcohol container, and marijuana possession.” Such interactions are common in both life and sport. Individuals make mistakes, display signs of recklessness, lose control, make cries for help, deny all of the above possibilities, and continue down the same path. Many times, however, individuals heal and recover and find redemption, and a transformation occurs.

Sometimes such a transformation starts with one step forward followed by a multitude of steps in reverse, never mind the forgivable two. And sometimes the laws are simply unfair, and the public punishes what is no more wrong than what is so often deemed right at a given moment in time. In the case of Mookie Blaylock, however, a series of dots was arising that if connected, suggested he was staggering down a rather dangerous path and either not receiving the support he needed or unwilling to accept the caution voiced by others as his own.

In high school, he had been suspended for marijuana use. Then, in 1997 and just off probation from the 1995 arrest that prompted a head coach’s lecture, he would be arrested again for marijuana possession. Again, such incidences occur often, and such incidences can be nothing. Christian Laettner’s own marijuana use would cross the line in the league office’s eyes during his late-career tenure in Washington, but there’s not a whole lot more to write on the subject. He paid a fine. He served a suspension. A lot of basketball players smoke pot, and since the late 1990s, a lot of jurisdictions have softened the laws surrounding marijuana use.

But Blaylock’s issues with marijuana went hand-in-hand with his alcohol use. He would eventually rack up approximately seven D.U.I.’s, culminating in tragedy. Eleven years after his playing career ended, Mookie Blaylock would suffer a seizure caused by severe withdrawals from alcohol. The seizure would occur while he was operating a motor vehicle he had been court-ordered not to operate, and his car would collide with another vehicle belonging to Frank and Monica Murphy. The consequences would prove fatal for Monica.

But who could see all that coming in the midst of the 1990s? The writing on the wall is often a great deal easier to read in hindsight. I started middle school in 1995, and I don’t remember exactly how the Atlanta-Journal Constitution covered Blaylock’s errors at the time, but I do remember the weight given to the sports section that day, and it didn’t hold quite the same mass as when OJ Simpson was on trial or when Lisa ‘Left Eye’ Lopes burned down Andre Rison’s house.

In 1995, Mookie Blaylock’s story didn’t seem to hold a victim other than himself and his teammates within the organization. I imagine that’s how the story played in public. Plus, Blaylock played everything close to the chest. Smith and later Mutombo were always the spokespersons for those Atlanta teams. But they were in many ways also atypical faces for a franchise: they were a few years away from personally funding hospital construction projects in the places that raised them. But no one could see that good on the horizon either. What could be observed on the court was a budding contrast between Blaylock’s cool glaze and the stoic uprightness of the team’s more vocal stars.

If the Atlanta Hawks were residing inside a glass house, then Blaylock’s enigmatic silences kept one watching longer than the obvious talents of Smith’s 3-point shooting and Mutombo’s shot-blocking, neither of which needed explanation. Blaylock, on the other hand, was the mystery, but I don’t think anyone watching this team knew just how much he was hurting and there was definitely no way to know how much that hurt would eventually harm others. More importantly, the team seemed largely at ease with the status quo, and no one was willing to pick up a stone, let alone toss it.

Some athletes long for a soapbox, but many desire no such thing. Mookie was a basketball savant with no code to follow but his own. That baller mentality that so often is ascribed to Kevin Durant used to be much more common. Many of today’s players are polished in the way that Steve Smith was polished. They possess media savvy to the point they host their own podcasts and lobby the public for attention. And that makes Blaylock both generations and personality types removed from the Draymond Greens and Kyrie Irvings of the world. Even Durant bristles in public. For Blaylock, the game really was the one thing, and everything else was unrelated.

But all four personalities appear in their differences to fear a lack of control over their own narratives and livelihoods. They all sense they are being distorted by all those that watch them do what only they can do. But doing that one thing in such a public forum seems to have filled Blaylock with an unbearable anxiety. Hence, all the attempted fixes: the smoking before games, the drinking while driving, the fishing for trout. There is a distrust for what others have to say and for how they will listen. There is a turning inward that can be as silent as it is loud, and that silence can cut like a knife.

While Mutombo might invite Ahmad Rashad and Summer Sanders to tour his Denver mansion for Inside the NBA or ask an electrifying question that lives on in folkloric perpetuity (like “who wants to sex Mutombo”), Blaylock was largely attempting to deaden his senses off the court. But those attempts eventually left him no margin for error in either place. Following the 1996-97 season Blaylock saw his Win Shares and VORP cut in half, and Atlanta really was no better than he was capable of being.

How high would these Atlanta Hawks fly?

How brief was this Atlanta team’s flight in the sun? The crowning achievement was stealing one game in a second-round series against the Chicago Bulls. In that brief moment, it appeared that a Mutombo-led team might pull off another miracle. Then the series was over as quickly as it began. In the seasons where Mutombo led the team in Win Shares, Atlanta made it to the Eastern Conference semifinals twice. That’s the same number of times the team made it in the years when Blaylock led the team prior to Mutombo’s arrival. In an age of finger-wagging, it felt like anything was possible. It felt like the South might have something to say — like Mount Mutombo’s peak might be one step from outer space. He had that effect on people.

In 1994, Mutombo’s Denver Nuggets were an eight-seed doomed to lose in the first round to the Seattle SuperSonics. But what was supposed to happen didn’t happen. The Nuggets boasted a roster that was youthful in all the right ways. The players were talented, but they also didn’t know their ceilings. The series would end in an exhausted overtime flurry and Denver’s franchise cornerstone clutching a basketball above his head while lying on his back. In the scene, the space between Mutombo’s upper and lower jaw is a fault line between laughing and crying. He looks as if he’s waiting for a bird of prey to swoop down and seize the basketball. He also looks unwilling to let it go.

The upset over Seattle ended up being such a great sporting moment because that’s all it was — a mosquito trapped in amber — , and every team that acquired Mutombo’s talents thereafter believed it could resurrect that same miracle. Mookie Blaylock and the Atlanta Hawks were chasing Jurassic Park-sized dreams. You wish it could have turned out some other way. The things left unsaid can outlast everything that was said out loud. You can be left scratching at those silences as if they were mosquito bites.

Check out more reflections in our NBA at 75 series and subscribe to The Whiteboard to make sure you keep up with all our latest NBA news and analysis.