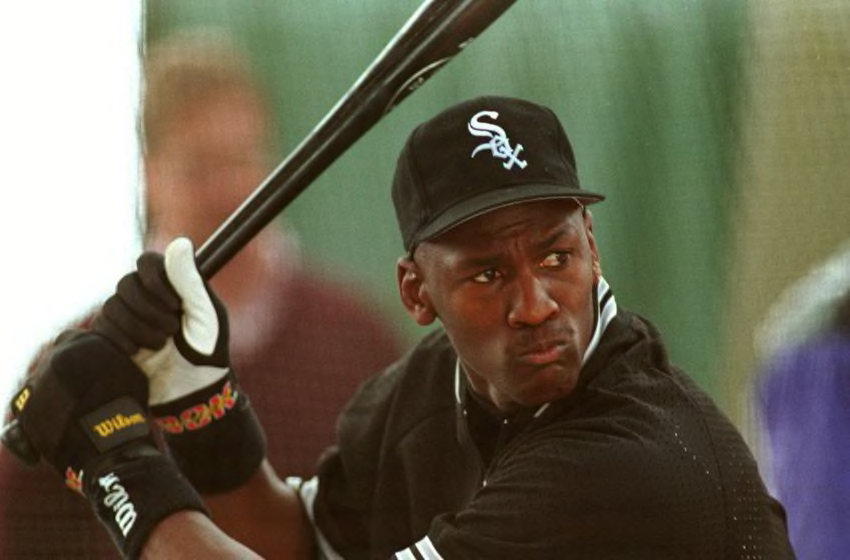

CHICAGO, IL – FEBRUARY 7: American basketball star Michael Jordan takes batting practice 07 February 1994 with the Chicago White Sox in a bid to play with their baseball team. (Photo credit should read EUGENE GARCIA/AFP via Getty Images)

In 1993, Michael Jordan gave up basketball for what seemed like an impossible dream: make it to the big leagues as a professional baseball player. Did he have a shot at reaching the majors?

By the end of the 1993 season, the mystique of Michael Jordan was at its peak. Jordan had just led the Chicago Bulls to their third straight NBA championship, averaging 41 points per game in Chicago’s six-game series victory over the Phoenix Suns. He was the best basketball player on the planet and the most famous athlete in America. He seemed to rise above everyone else, a man without any equals. But a life-changing event that August proved just how human he really was.

On Aug. 3, the body of Jordan’s 56-year-old father James was found in a creek near McColl, South Carolina. The elder Jordan had pulled his Lexus off the interstate to get some rest when he was attacked by two men looking for people to rob. He had been shot in the chest by a .38 caliber gun, the victim of a seemingly random, senseless act of violence.

James Jordan’s death devastated his son. Jordan began searching for ways to honor his late father and soon found one. James had been a semi-pro baseball player in his youth. He dreamt about his son playing not in the NBA but MLB. So that is what Michael decided to do.

On Oct. 6, Jordan told the Bulls they would have to continue their run for a fourth straight title without him; he was retiring at the height of his powers to pursue a career in professional baseball with the Chicago White Sox. Other off-the-court pressures weighed heavily on Jordan that summer: coming off his third title, the hyper-competitive Jordan had nothing left to prove in basketball, no worlds left to conquer. And multiple deep playoff runs, combined with playing in the 1992 Summer Olympics as a member of the ‘Dream Team,’ left Jordan exhausted. His basketball career appeared over; his baseball career, though, was just getting started.

Jordan’s arrival in White Sox camp the following spring brought with it a boisterous following. Fans lined the gate hoping to get a glimpse of him. But not everyone was excited to see him.

“He had better tie his Air Jordans real tight if I pitch to him. I’d like to see how much airtime he’d get on one of my inside pitches,” Randy Johnson, then with the Seattle Mariners, said.

Royals Hall of Famer George Brett believed most players wanted to see him fail: “I know a lot of players don’t want to see him make it, because it will be a slap in the face to them,” he said.

Sports Illustrated ran a cover that March that read, “Bag It, Michael! Jordan and the White Sox Are Embarrassing Baseball.”

Jordan’s chances of making it to the big leagues appeared bleak. He hadn’t played competitive baseball in 13 years. He had been an all-city stand out as both an outfielder and pitcher for Laney High in Wilmington but gave up the game in March 1981 when he committed to play basketball for Dean Smith at North Carolina.

But he showed early flashes of the same natural talent and drive that came to dominate basketball. In an exhibition game against the Cubs at Wrigley Field that April, he went 2-5 with two RBI. He started showing up two hours before practice to get in some extra time in the batting cage.

He was still raw, however, and the White Sox sent him to Double-A to play with the Birmingham Barons, managed by Terry Francona.

Jordan was 31 years old at the time, eight years older than the league average. He ended up hitting .202 in 127 games while stealing 30 bases but getting caught 18 times. He hit only three home runs in 497 plate appearances, but homers were hard to come by for most players in the Southern League that season. The entire Barons team combined to hit only 40 all season. Jason Giambi, who would go on to hit 43 home runs in the Majors six years later, had six in 229 plate appearances for Huntsville. Alex Rodriguez would hit 696 home runs in his big league career but had only one in 69 plate appearances for Jacksonville that summer.

Jordan struck out in more than a quarter of his plate appearances but managed to draw 51 walks. His walk rate of 10.3 percent was better than the average Major Leaguer (8.9 percent) that season. In the field, Francona started him in right field before realizing he did not have the arm to make long throws, switching him to left by the end of the year.

Following the Minor League season, Jordan was sent to the Arizona Fall League to compete against some of the top prospects in baseball. Nomar Garciaparra was his teammate with the Scottsdale Scorpions; a 20-year-old Derek Jeter played for the Chandler Diamondbacks. But all the attention was on Jordan.

“One game we played, there were probably 10,000 people there,” his teammate Chris Snopek told The Athletic. “The next night, they were retiring his No. 23 jersey in Chicago and he was gone. We got to the park there were probably 150 people at the game. That made us all feel real good on how valuable the rest of us were.”

His stop in Scottsdale, though, would be the end of his baseball career. The Triple-A Nashville Sounds were preparing for him to join the club the next year, but Jordan never made it. With the baseball strike that forced the cancellation of the 1994 World Series still going into the spring, Jordan realized he would not play for the White Sox that season; he had no interest in being a replacement player. On March 10, he announced his retirement from baseball and issued a brief, two-word statement about the Bulls: “I’m back.”

Would Jordan have made the big leagues if he continued in baseball? Opinions among people who saw him play differ.

“I would never say he wouldn’t have made it,” Scorpions catcher Chris Tremie told The Athletic. “The improvement we all witnessed over that year and the athlete he was and the work ethic he had, I think he would have had a chance. How long that would have taken, I don’t know.”

Another Scorpions teammate, Michael Tucker, though, believes he got started too late to develop into a real prospect.

“If you gave him two or three more years, he would have been a solid player. He may have gotten a chance because of who he was, but in the time frame he was trying to do all this in and the age he was, I don’t think it was going to happen,” he said.

One thing everyone agrees on is that he was clearly improving. A batter has less than half a second to get a rounded bat to meet a round ball that’s sliding, curving, cutting, and sliding. It’s hard enough for a player who’s seen tens of thousands of pitches over the course of their life. That Jordan struggled at first to do it after not playing for 13 years is understandable, but he started to get better.

While he barely cleared the Mendoza Line with Birmingham, he did hit .260 over the last month of the season. His average at Scottsdale was in the .280s before injuries started to take their toll; he finished the Arizona Fall League with a .252 average. When he found he was late to fastballs, he adjusted; when he struggled with curveballs, he focused on picking up the spin of the ball, something that comes naturally to a pro. And while he still caught the ball with both arms extended, like catching a football, he was starting to pick up the intricacies of playing in the field.

“He’s made a lot of improvement,” White Sox GM Ron Schueler told the Chicago Tribune that November. “When you think about it, it hasn’t even been one year since he started playing baseball. He still makes some mistakes, but his bat speed is better, and he’s learned things such as throwing to the right base.”

Jordan’s baseball odyssey lasted just one season. The odds were heavily weighed against him, but that hadn’t stopped him before. When he was cut from the varsity basketball team in his sophomore year in high school, he worked all summer to make himself into the best player in the state.

During his time as a baseball player, Jordan may not have been as skilled as the players he was competing against, but given time they would have found out something about him that players in the NBA had already discovered: never tell Michael Jordan he can’t do something.