It’s time for our first fall tradition: picking the six most intriguing players of the season. As usual, we (mostly) steer clear of superstars and rookies.

Jonathan Isaac, Orlando Magic

Orlando’s offseason plan for Isaac led him to a startling discovery.

“I did not know I could eat this much,” Isaac says. “My mind is blown. Eating is almost not enjoyable anymore.” Isaac says he has eaten five or six “real meals” every day to add heft to his string-bean frame — without compromising the quickness and switchability that hold All-Defense promise.

The Magic estimate Isaac has put on 15 to 20 pounds. That would mitigate his only major vulnerability on defense: brutes burrowing into Isaac’s chest, dislodging him, and lofting layups as he stumbles backward. Against some teams, the Magic toggled assignments so Aaron Gordon would defend behemoth power forwards — leaving Isaac to trail wings.

Jeff Van Gundy often had Isaac defend wings during practices with the USA Select team; during that camp, Isaac says he texted Pat Delany, an Orlando assistant, requesting Delany prepare film of players who were good at scampering around with wings. “I really don’t know how to read guys coming off screens,” Isaac says.

Isaac should become a stopper against every position. His combination of length and speed is outrageous. He reads the game well. What stands out already is an absence of mistakes — unusual for a player so young.

The other side will determine Isaac’s ceiling (All-Star or solid starter?) and whether the Magic’s ultra-big lineups can squeeze enough points for Orlando to chase home-court advantage in the first round.

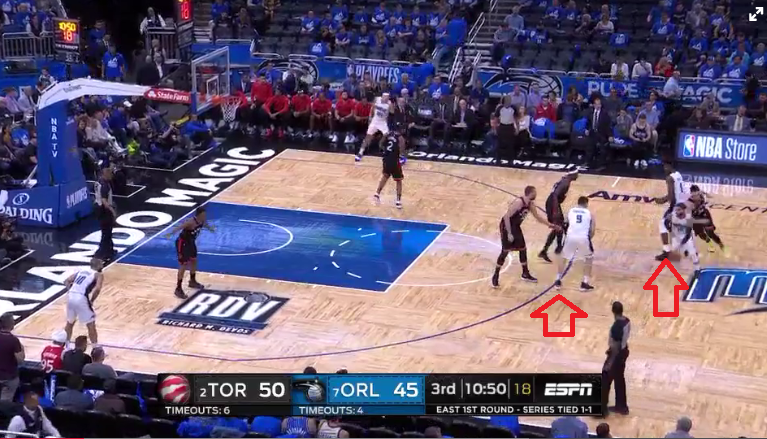

Isaac is never going to be a high-volume screen-setter alongside Gordon and Nikola Vucevic. He lives off the ball. Isaac shot 38 percent from deep after the All-Star break last season (kindly ignore his 4-of-20 mark in the first round of the playoffs against Toronto!), and carrying that over is one of Orlando’s most important swing factors.

Opponents are going to ignore Isaac, clogging up everything else, until he proves he can punish them. Forcing defenders to guard him more closely would unlock a surprisingly nifty pump-and-go game. Isaac can handle lefty and righty, and see the next pass:

(He still settles for too many pull-up 2-pointers.)

Isaac is only so useful loitering around the arc. He has good timing as a cutter, but the Magic rarely found him; Isaac would often slip open toward the rim, raise his arms, and continue with polite dejection to the other side. Cutting also slides Isaac into offensive rebounding position, and the Magic — 22nd in both scoring efficiency and offensive rebounding rate — could use extra juice there:

He would be a threat hanging in the dunker spot. He can dive to the rim when he and Vucevic set staggered screens:

Opponents will switch, wagering Isaac can’t hurt little guys in the post. Isaac averaged just 0.54 points per possession on post-ups, second worst among 166 players who logged at least 25 such plays last season, per Second Spectrum. Bulking up should help. The apex version of Isaac should dust traditional power forwards and score over wings — denying opponents the luxury of tailoring frontcourt matchups to stop Gordon.

“I think there will be more post-ups,” Isaac says. He has dipped his toe into bringing the ball up and running a two-man game with Vucevic. He flashes finesse that catches you off-guard, with loping Euro-steps and soft floaters.

“I feel like I can do everything,” he says.

Isaac exists in a state of tension with many of Steve Clifford’s central tenets. Clifford’s teams have historically punted on working the offensive glass to get back on defense. Isaac should be a weapon in transition, but Clifford’s teams are cautious there; defensive rebounding comes first. “I’d like to get more leak-outs, but we don’t do that much,” Isaac says. Random cuts muck up spacing.

Tension is healthy. The Magic need a dose of wildness. They need methods of scrounging points beyond their intricate half-court system. By not precisely fitting in, Isaac can round out the Magic.

It’s hard to overstate how much the Magic love Isaac. They have batted away any Isaac trade inquiries, sources say. He has quickly become a standard-bearer of the culture president Jeff Weltman and GM John Hammond want to nurture.

Isaac’s younger brother, Jeremiah, 11, is almost part of the team. He is always around the facility, and makes regular rotation suggestions to Clifford — not always in favor of his brother, Clifford says. Weltman even let Jeremiah call in Orlando’s picks to the league office during the draft. He practiced pronouncing Chuma Okeke‘s name all day, Isaac says.

Orlando is betting on Isaac’s work ethic. Most players return home after doing local media the day after being drafted. The Magic expected Isaac to do the same in 2017. Instead, he asked whether coaches were around that weekend; he wanted to start work.

That story has stuck with higher-ups. They hope the payoff is coming.

Mitchell Robinson, New York Knicks

Robinson burst onto the scene as the rare big man with the fast-twitch explosiveness to regularly reject jumpers — a potential second-round steal for the Scott Perry/Steve Mills regime. He obliterated 22 3-pointers, five more than any other player, in just 1,360 minutes. There are maybe two living humans who can do some of the things Robinson does on defense.

He also fouled the bejesus out of everyone. Clever ball-handlers baited him with eyebrow fakes and give-and-go trickery:

New York’s coaches have hammered in a simple message: Be the second jumper. Don’t leave your feet until you see the other guy get air.

“I hear that,” Robinson says. “But with some guys — Steph Curry, James Harden — you can’t wait.”

Jumping too late can be a problem around the rim. Robinson sometimes leaves the glass naked hunting no-chance-in-hell blocks.

Robinson cut his foul rate toward the end of the season, but it was still too high — and not just the result of hyper block-chasing. Robinson needs to hone his fundamentals. He defends the pick-and-roll with his hands at his sides, exposing passing lanes.

“That can be fatigue,” he says. “When you’re tired, you drop your arms.” He reaches and hand-checks. He tries to blow up pick-and-rolls by shoving the screener — a gambit he says he learned from Amar’e Stoudemire — but refs caught on. “I can’t get away with it every time,” he says.

He is not as good as he should be covering both ball handler and roller at once. He sometimes takes poor angles. His footwork can be mechanical:

Robinson has shown progress, but it may take longer than optimists expect.

On offense, he is a raw rim-runner thirsty for lobs. (You can sometimes catch Robinson leaping for a lob when no one has thrown one.) He seldom sets actual screens, preferring to slip early into the lane. He sometimes rolls full speed with his head down instead of starting and stopping to make himself a target. New York seemed fine with most of that, and Robinson sucks in a ton of attention — creating open looks for shooters.

Laying the wood now and then would be nice, though. Teams learned Robinson’s tendencies, and started moonwalking in sync with him:

They also switched some, daring Robinson to beat them on the block. He couldn’t. The Knicks scored just 0.79 points per possession on any trip featuring a Robinson post-up — third worst among all players, per Second Spectrum tracking.

He fared well enough when he played amid decent shooting. The Knicks compromised that by signing Julius Randle, Taj Gibson, Bobby Portis and Marcus Morris. Robinson will rim-run into walls.

Randle and Robinson can run some big-big pick-and-rolls. Randle will bulldoze one-on-one, draw help, then drop the ball to Robinson for dunks. When he’s not involved in the pick-and-roll, Robinson is dangerous lurking along the baseline; Dennis Smith Jr. likes finding him there:

The Portis-Robinson pairing intrigues; Portis shot 39 percent from deep last season.

Robinson anticipated the need to evolve. “I’m going to shoot midrangers, maybe a couple of 3s,” he says. He has started practicing basic playmaking from the elbows, though he concedes his jumper has been a higher priority. It is unclear what Robinson might do if opponents trap New York’s point guards on the pick-and-roll, and force them to hit Robinson far from the rim. He averaged about half an assist per game.

But Robinson represents a reason for hope after New York’s free agency whiff.

Russell Westbrook, Houston Rockets

It might be the most interesting question going into this season: What is Westbrook going to do when James Harden has the ball?

He has to shoot better, for one. He can’t cut and screen and dart inside for offensive rebounds and do all the sexy-nerdy basketball things on every possession. The game doesn’t flow that way for most stars. Westbrook has hit about 35 percent on catch-and-shoot 3s in some prior seasons; he could bounce back to that kind of acceptable, non-grisly number on the looks Harden will feed him.

But Westbrook has to do a lot more of that sexy-nerdy stuff for this bizarro partnership to take Houston as far as the Harden-Chris Paul version got them in 2018. Westbrook has done almost none of that. He is the battering-ram-on-repeat who drove stars out of Oklahoma City. Playing with Harden — a superior on-ball scorer in every sense — provides a chance for Westbrook to rewrite the narrative of his career.

He’ll still have the ball a lot, of course. Westbrook can reanimate a zombified transition game and thrive running spread pick-and-roll in the sort of spacing Oklahoma City rarely gave him. Harden has to play off the ball more, too.

But Westbrook has never been his team’s secondary ball handler. If he spends his off-ball time chilling behind the arc, hands on knees, the Rockets have little chance to come out of the Western Conference.

Jerami Grant, Denver Nuggets

Grant spent five seasons in two strange places: the Process Loss Factory in Philadelphia, and the Westbrook show in Oklahoma City. He adapted to each, but you always got the sense he could grow into a different sort of player — the player he should be, not the one teams tried to manufacture — in the right environment.

The Nuggets are betting they have that environment because they have Nikola Jokic, the greatest passing center in modern NBA history. They spent a year-plus scouring the league for a power forward of the future — someone Jokic’s age, who fit Jokic’s game, says Tim Connelly, Denver’s president of basketball operations. They zeroed in on Grant and one other player they could not obtain. If they are right, and some actualized version of Grant is waiting to emerge, the Nuggets should be really good for a long time.

Connelly called Grant after finalizing the trade and told him: We want this to be home. “That made me feel real comfortable,” Grant says.

Jokic texted Grant a welcome message from overseas. Grant, a film buff, began watching clips of Jokic’s passing. He was giddy. Grant is a cagey, explosive cutter, but the Thunder mostly had him stand around the perimeter. The paint belonged to Steven Adams.

Grant survived. He shot 39 percent from deep. When slower defenders contested his shot, he could pump-and-go by them.

Most of Grant’s individual work has centered on fixing that jumper. In Philadelphia, he would ask shooting coach John Townshend to meet him at the practice facility for 6 a.m. workouts, both recall.

The Sixers also tried to break Grant’s habit of dunking everything. “We are talking violent dunks in every drill,” says Billy Lange, a longtime Sixers assistant who is now head coach at St. Joseph’s University. “You could almost feel them across the whole facility.” Lange pulled Grant aside during one pregame warm-up and asked if he knew what peanut brittle felt like. “Hard,” Grant replied. “What happens if you drop it to the ground?” Lange asked. “It shatters,” Lange told him. “That is your foot. Every time you dunk, you are hurting your foot a little.”

“I think about that to this day,” Grant says.

Grant tried to keep Philly’s locker room afloat amid historic losing. “We have to take our craft more seriously,” he would remind young players, Lange says. The losing took its toll in Grant’s second season, when Philly went 10-72. Grant grew sullen. He drifted away from the practice facility that summer.

When the Sixers traded Grant to Oklahoma City early the next season, coaches felt a combination of sadness and relief that he might win, they say now.

“We went through all the s— we went through, and he came out unscathed on the other side,” says Sixers coach Brett Brown.

Grant became a full-time starter and signed a three-year, $29 million extension with a player option for next season — a deal Grant has called “a bargain” in conversations with confidants, he and others say.

But Grant as a stretch power forward in Westbrook’s offense was a square peg/round hole contortion. Defenders strayed from Grant even as his percentage ticked up, laying in wait for his drives:

Grant scored only 0.89 points per possession on drives, one of the worst marks in the league, per Second Spectrum data. He can make functional passes in space, but misses the advanced reads that really puncture defenses. Look at Paul George on the right wing begging Grant to hit Nerlens Noel under the basket:

His first step isn’t as quick as you’d think — occasional indecision doesn’t help — and Grant can get caught in the air with no place to go:

In Denver, Grant can bob and weave while Jokic surveys from the elbow. He can screen for Jamal Murray as Jokic spaces the floor as an outlet — waiting to touch a pass to Grant flying down the lane. He can set improvised picks for Jokic in semi-transition. Playing with better shooters makes everything easier. Driving corridors widen. Passes lanes stay clearer, longer.

On defense, Grant can switch across every position, cover Jokic’s weaknesses, and protect the rim. Any team built around Murray and Jokic needs strong defenders at the other three positions.

It will be interesting to see how Mike Malone juggles minutes. Paul Millsap is the deserved starter. Grant can work as a backup center, but Mason Plumlee — that’s Team USA stalwart Mason Plumlee, mind you! — killed it in that role last season. Both Juancho Hernangomez and Michael Porter Jr. can play some small-ball power forward. We may even see Grant, Millsap and Jokic together when Denver faces LeBron James and Kawhi Leonard — with Grant guarding those alpha scorers.

“I’m excited to see how he fits,” Lange says. “If he cuts with the same violence he dunks with, he’s gonna get a lot of easy baskets.”

JaMychal Green, LA Clippers

For a relative unknown, Green could play a pivotal role in the title chase. The Clippers are thin in traditional big men, and have none with Green’s ability to shapeshift between lineup types. He may start at power forward, play center after Montrezl Harrell‘s first stint each half, and log heavy minutes alongside Harrell.

Green was dejected when the Clippers acquired him from Memphis last season; he thought LA was tanking after dealing Tobias Harris and he would not get much playing time, he says. He sulked. (Green is quiet by nature. Chatty Memphis veterans took to him because he never spoke, higher-ups there recall.) Doc Rivers and Sam Cassell gave him pep talks, he says.

Two months later, he was starting as a floor-stretching center against Golden State in the playoffs. Then, he dangled for two weeks in free agency. He passed on richer offers from several teams, including playoff mainstays, according to Green and sources at those teams. The Clippers had shown faith in him. Green is loyal. He has stuck with his agent, Michael Hodges, since the start of his career, even when bigger fish tried to poach him. (When those agents call, Green secretly lets Hodges listen in on their pitches, he and Hodges say.)

Kawhi Leonard texted Green after joining the Clippers and urged him to re-sign, promising “this sacrifice will pay off,” Green says.

Winning will get him paid down the line, Green says. Green has played the long game before. He was ready to give up on the NBA after the Spurs cut him just before the 2014-15 season. He had an overseas offer for about $500,000. Hodges pushed him to turn it down and give the D-League one more shot — to stay closer to his NBA dream. Green reluctantly agreed. He made the D-League All-Star game, and the Grizzlies signed him in February 2015.

In Memphis last season, it appeared Green had lost a step. He was hesitant jacking from deep, and Green doesn’t have much of a role without a reliable 3-pointer. He bumped up his attempts in LA, and coaches want even more.

He looked comfortable again in LA switching onto smaller players — one good performance hounding Luka Doncic stood out to coaches — and we may see more of that. He has years of experience guarding Anthony Davis. He may play a lot of crunch-time defensive possessions.

If Green hits — if he can spread the floor for Harrell and Ivica Zubac, defend multiple positions, and hold his own on the glass in small-ball lineups — the Clippers become a different team: deeper, more versatile. If he sputters, they will search out help.

Luke Kennard, Detroit Pistons

There may not be a team that needs a role player to pop as badly as the Pistons need Kennard to establish himself as an above-average wing. That won’t happen on defense. Detroit hides Kennard on the least threatening opposing players. His off-ball rotations can be scattershot. He is the rare player — joining fellow Duke sniper JJ Redick — with a listed wingspan shorter than his height.

The jump has to come on the other end, where Kennard showed major progress as a herky-jerky pick-and-roll maestro late last season and in the playoffs. “I didn’t know he was this good with the ball,” says Detroit coach Dwane Casey.

Kennard doesn’t get it as much sharing the floor with Blake Griffin, Andre Drummond and Reggie Jackson — one reason Casey says he may bring him off the bench again. Kennard ran just seven pick-and-rolls per 100 possessions with Griffin on the floor, per Second Spectrum. That number tripled to 22 without Griffin.

He has not shown the ability to work as a turbocharged, roving catch-and-shoot menace like Redick, Kyle Korver and Wayne Ellington. “He’s more useful with the second unit,” Casey says. (That second unit now includes Derrick Rose, who needs the ball a ton.)

Still: Kennard and Griffin have untapped potential for a spicy two-man game. Kennard has a little Bradley Beal in him — a knack for dancing back and forth as Griffin holds the ball at the elbow, and then cutting in unpredictable directions. “We have been repping that this summer,” Kennard says. “We are getting comfortable.”

He has the craft to shoulder more pick-and-roll duty. He jukes away from screens before going around them, pins defenders on his back, and slings smart passes with both hands:

But he can be tentative, pulling up for long 2s when he still has runway:

(Keep an eye on that last action. Detroit has only scratched the surface of the Griffin-Kennard pick-and-roll.)

Kennard attempted just 61 free throws last season. He barely got to the rim, and flung up panicky floaters when he did. “I’ve really been focusing on my finishing,” Kennard says. Detroit’s cramped spacing didn’t help — Kennard saw a forest of bodies anytime he approached the paint — but that problem isn’t going away.

He’s not quite quick enough to burn brutes on switches. One solution: a step-back 3. Kennard has ultra-range, but he attempted only one pull-up 3 per game. He looked uncomfortable firing off the bounce, even when he had pried open some space with a mean dribble:

One culprit: a slow release. This can’t happen:

Defenders ran Kennard off the line even if he caught the ball with 15 feet of empty space in front of him. Kennard and assistant coach D.J. Bakker have worked on being in shooting position — hands out, knees bent — before the ball arrives.

“I am dialed in on getting my shot off quicker,” Kennard says. “I dissected film this summer like I never have before.”

Spot-up shooting may end up Kennard’s only “A” skill. He lacks the speed and explosiveness of most elite ball handlers — true No. 1 option types. But if he gets a little better at everything, including adding a dash of Redick-style off-ball motion, he can transform into a different player.